On April 5, 2012, the “Jumpstart Our Business Startups” or JOBS Act took its first breath with a stroke of Obama’s pen.

Appealing to the obvious cross-aisle interest in helping small businesses succeed by loosening certain securities regulations, the bill’s language outlined the methods it intended to either streamline or set aside.

Community banks — locally owned, operated, and with a focus on families and small businesses — were permitted 2,000 shareholders, up from 500. Startups were freed from specific regulatory requirements for a period of five years after they go public.

As far as democratizing business is concerned, the JOBS Act did a pretty good job in bringing Wall Street down a notch.

The JOBS Act came along two years after the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, a bill that also had the plight of Main Street in its sights.

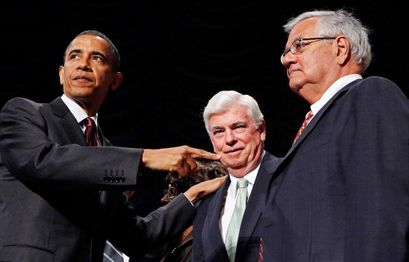

Signing the bill into law on July 21, 2010, Obama spoke to the issues that led to Dodd-Frank like a mariner recalls a storm.

“After taking office,” he said, “I proposed a set of reforms to empower consumers and investors, to bring the shadowy deals that caused this crisis into the light of day, and to put a stop to taxpayer bailouts once and for all.” Applause rang throughout the Ronald Reagan Building, perhaps the least vociferous response at the time from a nation that had been all but fiscally gutted.

“Today, thanks to a lot of people in this room,” he continued, drinking in the moment, “those reforms will become the law of the land.”

And in principle, at least, he was right. Dodd-Frank effectively established a system to counter the existing process on Wall Street, ending the unregulated orgy that, by way of a derivatives free-for-all and predatory lending, brought the entire United States economy to the brink of catastrophe.

Risks in the system would be closely scrutinized by its own oversight committeee; regulatory agencies would be consolidated; even the Federal Reserve would need to get Treasury approval before embarking on credit extensions. With 16 titles in total, Dodd-Frank compelled regulators to create a raft of new rules for Wall Street — 243 in all.

In short, the party on Wall Street was over. Or so the bill was sold, at any rate.

Immediately after Dodd-Frank’s passage, it didn’t take long for a general, if loose, consensus to emerge among observers on both the right and the left — a feat in itself at the apex of the Tea Party.

On one hand, you had conservatives worrying that new regulatory measures would strangle an industry seeing record profits in 2010. On the other, you had liberals wary of the business-as-usual organizing under Dodd-Frank’s surface, noting how little had actually changed among the key players behind the scenes. In either case, there was the suspicion that Dodd-Frank would be a back door route to the same old problems.

“The same regulators who ignored consumer advocates’ warnings about predatory lending have veto power over the consumer agency,” John Taylor, CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, told the Wall Street Journal that year. “That club of regulators is very insular, and usually in agreement.”

What really shook both sides of the aisle, though, was one of the most controversial proposals put forward under Dodd-Frank. In short, it would ensure that banks of a certain scale — like, let’s say, Lehman Brothers or AIG, the first dominos to fall in 2008 — wouldn’t be aided by public coffers in the event of their fiscal collapse.

As the text of the bill states, “financial companies put into receivership shall be liquidated,” and no “taxpayer funds shall be used to prevent the liquidation of any financial company under this title.”

These banking goliaths would be carved up into smaller, more manageable pieces under the Orderly Liquidation Authority of the Act, and as a result, would require none of the taxpayer bailouts that dominated headlines between 2008 and 2010. In preventing taxpayer bailouts, Dodd-Frank ostensibly dispels the overall myth of “Too Big to Fail.”

In a way, its impact on Main Street is a weird flipside to trickle-down economics. Here, what is intended to help small businesses and community banks are the systemic changes happening behind the scenes, those Sisyphean efforts at stopping broad-level fiscal corruption with eventual benefits for all things local.

But in imposing greater regulation, critics say, the same superstructure is choking or otherwise gumming up the works at the local level. And with four out of five major banks still teetering at the brink, according to the Wall Street Journal, some of those criticisms question whether small businesses and small banks will feel any positive change at all.

“If the Orderly Liquidation Authority is functioning properly,” writes Ryan Caldbeck, a private equity investor and contributor to Forbes, “President Obama is correct that Dodd-Frank prevents the taxpayer bailouts that are synonymous with too big to fail.

However, the operative word in the previous sentence is if, because to date, the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Coropration, the federal body tasked with investigating the soundness of financial institutions) has not developed the operational capabilities to carry out orderly liquidation.” In theory, it’s a great idea; in practice, unproven.

As far as the same regulatory labyrinth having an unduly oppressive effect on Main Street as it does on Wall Street, though, Caldbeck is quick to point out that the math is thus far inconclusive. “While community banks’ return on equity remains well below pre-crisis levels,” he writes, “ROE has rebounded from -2.8% in 2009 to 8.4% by year-end 2011, and as Gary Corner of the St. Louis Fed notes, community banks’ ROE has been in a decade-long decline.”

“Thus,” he concludes, “while some estimate Dodd-Frank gives big banks up to 50 basis points funding advantage, the overall effect of the SIFI designation (significant financial institution, otherwise known as a bank “too big to fail”) on small businesses and the community banks that fund them appear limited.”

The JOBS Act, of course, with its provisions targeted specifically at small businesses, has so far yielded actual results to encourage and stimulate growth.

But it’s a bill meant to correct a problem, to undo a specific knot that has kept a system of fiscal corruption in place far too long, with very real, very hurtful impacts on the local level. The JOBS Act addresses the symptoms; Dodd-Frank, if anything, tries to attack the root. The difference, critics suggest — a difference acutely felt by communities — is that the latter ultimately doesn’t do enough.

It’s sad, but perhaps in seeking actual results from Washington or Wall Street, it’s best not to hedge any bets on a bill concerned principally with Washington and Wall Street.